A merchant cash advance (MCA) is a type of alternative business financing that provides companies with quick access to capital in exchange for a portion of their future sales. Unlike a traditional loan, which has fixed monthly payments and an interest rate, an MCA functions more like a cash advance against expected revenue.

The provider advances a lump sum of money to the business upfront, and repayment is made through a percentage of daily or weekly credit card sales or bank deposits until the agreed-upon amount is repaid. This amount typically includes the advance itself plus a fee, known as the factor rate, which is different from interest and can make the total cost of borrowing significantly higher than conventional financing.

Because repayment is tied to sales volume, payments fluctuate: during high-revenue periods, businesses pay more, and during slower times, they pay less, offering flexibility but also prolonging the repayment period if sales decline. MCAs are often marketed to small and medium-sized businesses that need fast funding, have limited credit history, or may not qualify for traditional bank loans.

However, while they can provide immediate working capital for expenses like payroll, inventory, or expansion, they are generally considered one of the most expensive financing options and should be approached with careful consideration.

How Does a Merchant Cash Advance Work

A merchant cash advance follows a structured process that determines how businesses receive funds and repay them. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: Application and Approval

The business applies for a merchant cash advance and provides recent bank statements, credit card processing records, and basic financial information. Approval is usually based more on sales performance than on credit score, making it accessible for businesses with limited credit history.

Step 2: Receiving the Advance

Once approved, the MCA provider gives the business a lump sum of cash upfront. This amount is typically smaller than traditional loans but designed to provide quick working capital for urgent needs like payroll, inventory restocking, or unexpected expenses.

Step 3: Setting the Factor Rate

Instead of charging interest, MCA providers apply a factor rate, usually expressed as a decimal (e.g., 1.3). The repayment amount is calculated by multiplying the advance by this rate. For example, a $50,000 advance with a 1.3 factor rate would require $65,000 in total repayment.

Step 4: Repayment Through Future Sales

Repayment is made automatically by withholding a percentage of daily or weekly credit card sales or bank deposits. This percentage, called the “holdback rate,” continues until the full repayment amount is collected. Payments adjust with sales volume—higher during busy times, lower during slow periods.

Step 5: Completion of Repayment

Once the agreed-upon repayment amount is fully collected, the obligation ends. If sales were strong, repayment may finish quickly; if sales lagged, repayment takes longer. Some providers also allow early repayment, though this doesn’t always reduce the total owed since the factor rate is fixed.

Main Repayment Methods of Merchant Cash Advance

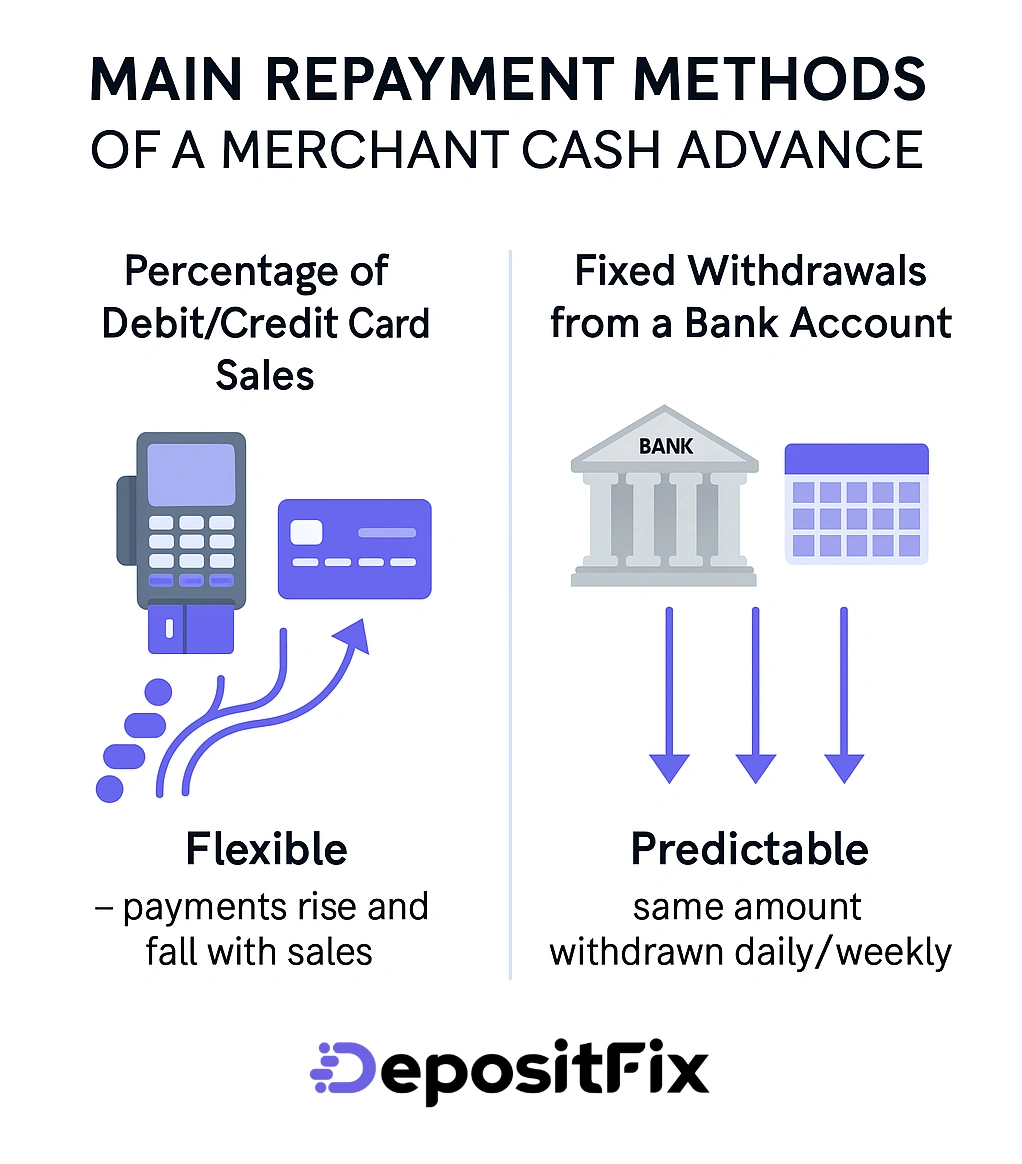

When it comes to repaying a merchant cash advance, providers typically use one of two methods. Each has its own structure and impact on a business’s cash flow.

Percentage of Debit/Credit Card Sales

Here, the provider collects repayment and withholds a fixed percentage of the business’s daily credit and debit card transactions. The more sales the business makes, the more it pays that day, and vice versa. This approach provides flexibility, as repayment aligns with revenue fluctuations, making it less risky during off-seasons or slow weeks.

Fixed Withdrawals from a Bank Account

In this method, the MCA provider takes out a set amount of money from the business’s bank account on a daily or weekly basis through ACH (Automated Clearing House) transfers. The repayment amount does not change, even if sales are lower that week. This method offers predictability but can strain cash flow during slow periods.

Merchant Cash Advance Rates and Fees

Merchant cash advance rates and fees work differently from traditional loans and are often higher, which is why MCAs are considered one of the most expensive forms of financing. Instead of charging interest, providers use a factor rate, commonly ranging from 1.1 to 1.5, that determines the total repayment amount.

For example, an advance of $40,000 with a factor rate of 1.3 means the business must repay $52,000, regardless of how quickly it’s paid off. Unlike interest rates, factor rates don’t decrease over time, so there’s no benefit to repaying early.

In addition, providers may charge administrative or origination fees, further increasing the cost. When these costs are converted into an equivalent annual percentage rate (APR), they can easily exceed 40% to 100%, far higher than bank loans or even credit cards. For businesses, this means that while an MCA offers speed and accessibility, the long-term financial burden should be carefully weighed before committing.

How to Calculate the Cost of a Merchant Cash Advance

Calculating the cost of a merchant cash advance is different from figuring out a traditional loan because it uses a factor rate instead of an interest rate. To determine the total repayment amount, you multiply the advance amount by the factor rate.

For example, if you receive a $50,000 advance with a factor rate of 1.3, you’ll repay $65,000 in total. The difference between the two, $15,000 in this case, is the financing cost. Unlike loans, this cost is fixed, meaning even if you repay faster, you won’t owe less.

To get a clearer picture of the true expense, many businesses convert the cost into an equivalent APR (annual percentage rate). This involves taking into account the repayment period and how often payments are deducted from sales or your bank account.

Because repayments are made daily or weekly, the effective APR of an MCA can be extremely high, often ranging from 40% to over 100%.

A merchant account lets businesses accept card payments, holding funds temporarily before depositing them into the main business bank account.

A merchant agreement defines how a business accepts card payments, covering fees, settlement, chargebacks, and compliance with the payment processor.

Ready to streamline your payment operations?

Discover the hidden automation in your payment, billing and invoicing workflows. Talk to our experts for a free assement!